Category: English

Ross Daly with Huun Huur Tu & The Trio Chemirani – White Dragon “To Moiroloi tou Orfanou” (Το μοιρολόι του Ορφανού)

How’s this for change? Sitting for tens of hours at the computer working on the FINAL STRETCH in the middle of August is certainly beneficial to my musical escapades! Back to work…

Why do we hate seeing photos of ourselves?

Reposting from io9.com just because I thought it was such a simple answer to such a common issue. A little primer video:

Review: The Flinch

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Quote from near the end of the book: “At this point in most books, the authors promise you that if you do what they say, you’re sure to succeed.

In this case, you’re sure to fail. To be rejected. To discover wrong paths. To see what

humiliation is like, firsthand”…

Me, after reading the above:I don’t like it, it sounds dangerous…”

…”You’re sure to live.

And then yes, maybe, you might reach your goals.

Would you have it any other way?”

So, is The Flinch a book or not? In theory, it is; to me, all it takes for a book to be a book, apt for review here on Goodreads, is for it to call itself by that name — being an actual bound edition is becoming more and more passé, so let’s stick to what we’ve got. In practice, however, it’s not really one: it could have been an exceptionally long post on some forum or an article on a site like High Existenceor 30 Sleeps. If you ask me, it makes no difference at all: what’s important here is the information.

The Flinch strikes at human instinctive self-defense mechanism — the out-stretched palms hiding one’s face from the… face of danger — taken to less physical domains of existence, such as talking to strangers, taking plunges off of various heights or simply doing anything that might challenge our comfortable status quo. The book says that when we feel our all trying to prevent us from doing something (and we can’t find any good, logical reason not to do it if we ask ourselves “what am I really scared of?”), it’s probably others people’s fears, prejudice and/or experience kicked into us: from parental overprotection to serial-killer ward to “a frined of mine once…” to cold, hard facts of life.

The things is though that if we follow everyone else’s advice we never get to experience anything for our own, we never get to face our fears and know ourselves a little bit better, much less create ourselves into what we’d dream to be. We never get to take life to the next level, and then the next. While it may be true that some, if not few, of society’s fears we’ve taken up would be good to keep in mind at all times, I’ve found from whenever I’ve fought The Flinch that it never was all that bad. On the contrary — who knows what having learned to pursue a comfortable, flinchy front might be robbing me from daily?

It was a good, short, crisp read that filled me with inspiration which will probably prove to be short-lived as with other writings of similar kind but I hope I keep it with me and remember its lesson for long.

Here is a link for you to read it. It won’t take you very long and you will come out of it thoughtful and hopefully empowered.

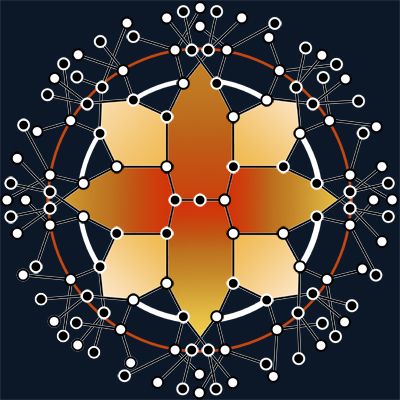

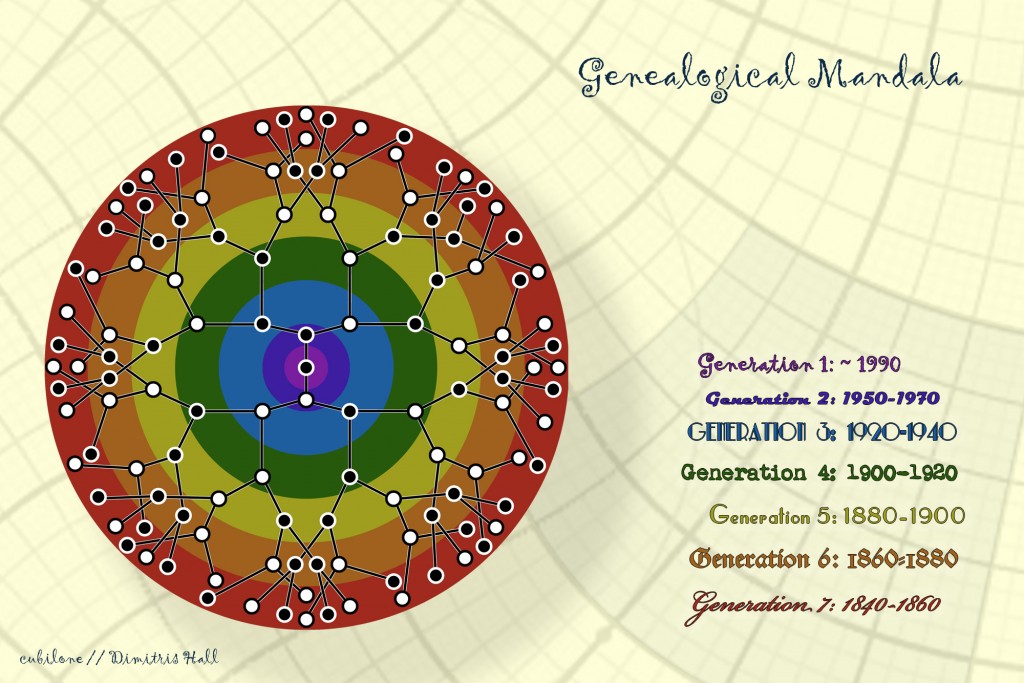

Genealogical Mandala

Translated by yours truly from the original article in Greek:

http://hallografik.ws/archive/?p=2775

How many were there of your parents? 2. Of your grandparents? 4. Of your great-grandparents? 8. Of your great-great-greandparents? 16.

How many generations until we reach 64? Only 7, going back roughly 150 years, if we assume that every birth comes 20-25 years after the last. At 10 generations back, not too long before the Greek Revolution of 1821, this number reaches 512. If we go another 10 generations back and touch the early 16th century, when the Ottoman Empire was at the peak of its power with Suleyman the Magnificent at its reins, when America had just started being conquered by the Spaniards and when Michelangelo Buonarroti was sweating under the ceiling of the Capela Sistina, the number of your great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandparents alive at the time will have already exploded to 1,048,576. At this rate, of course, and if we take into account that we humans have existed as a species for over 100,000 years (even if we steer clearly away from counting our humanoid ancestors, and before them the Common Ancestors, and before them some obscure mammals, and before them some synapsid and his lot and the beat goes on), it doesn’t take long to reach trillions of individuals and beyond, extraordinary numbers that humanity never saw, even if we put all the homo sapiens that ever lived in its history and prehistory together! To be exact, it’s said or theorised (which doesn’t count as much if you get down to it) that all of us are descended from a small group of homo sapiens that survived the last Ice Age. The answer to this apparent mystery is that there has simply been a lot of incest around — incest that we would probably not even count as such. If my great-great-great-greatgrandfather from my mother’s side was the brother of my great-great-great-great-grandmother from my father’s side, it wouldn’t remotely count as incest, etc.

Our genealogy is as mysterious and magical as is our history: we know, we can know so little about it, that we easily fill in the rest using our imagination’s colourful palette. As we do with anything unknown and mysterious, that is to say with everything.

The matter is definitely a chaotic mess. I shall incist however on the initial number. 7 generations, 64 ancestors. It seems to me like the perfect combination of control and proximity: were it larger it would soon be out of control and any form of sense of closeness to those distant ancestors would be lost; any smaller and we would lose most of the magic and complexity lying therein. Not to mention that 7 and 64 are nice, round, culturally powerful and significant numbers that please the eye, our aesthetics, and that thing deep inside of us that complains when a frame is crooked or that makes us wait observantly for the split second in which the green and red lighthouses at the entrance of the port will synchronise their flashes of different frequency.

Let us cut to the chase. In my experience, when talking nowadays about genealogy we use two terms: trees and families.

As usual, I have my objections.

The idea of using trees to describe a family when we ourselves are the trunk, as in the image above, seems strange to me. Family trees would be OK in the representational sense if we were the trunk, our roots were the ancestors and our branches and leaves were our descendants. I have never, however, seen such a tree being used for this purpose.

Next is the family, the surname. There’s something of the question “where do you come from?” nesting in their use. It took me years to understand that this question is generaly translated as “where’s your father from” and to tell you the truth, I’m not at all sure whether “from Australia!” has been the answer that all who have asked me have wanted to know, despite the almost unbearable honesty of the reply. I was born, raised, and live in Nea Smyrni, Athens, Greece, after all!

Perhaps this is happening for the same reason surnames sport certified name of origin characteristics; tell me your surname so I can tell you who, or at least where from, you are. That’s certainly half the truth — or to be exact, much, much less than half of it: only men in the genealogy share the surname, with women losing themselves in this mixture like salt in water. Many family trees even study their family’s history not based on the people but on the name, especially in older times and in noble dynasties, trying to find everyone that shares that name and are relatives or descendants, without however giving much notice to the women that joined, and still do, the family, perhaps only because of the sheer necessity of the matter. Besides, I believe it’s relevant that in much of history, definitely in Christian and Muslim history, men wanted sons so that their family as reflected through their name could endure throughout the ages.

Thus I wanted to portray the above and more in some creative and imaginative way. What I ended up with is this (as you must have noticed at the top of the article):

Why mandalas?

Mandalas are radial, symmetrical shapes, symbols of wholeness, cyclicity and at the same time of the moment, the greatness and insignificance of the now, at least in the context of the philosophy that gave birth to them, Hinduism and later Buddhism. Carl Jung was deeply inspired by them: he used to ask of his patients to draw mandalas and he later used the results as aids for his diagnoses. He believed that within the symmetry and the shapes there was a sequence to be found, a meaning to be discovered behind the use of the various drawings that they comprised. The uniqueness that emerged was, he believed, the essence of the individual him-or herself.

This clean-cut geometricity indeed has something soothing and wholesome about it; I can’t describe it any other way. Furthermore, the concepts of repetition and expansion and the one significant centre fit genealogy like a glove.

Not to mention mandalas can be stunningly beautiful.

Symbolisms

The symbolisms behind genealogy under the prism of the mandala are many and will vary depending on the person. The ones I choose, the connections I discovered that I found inspiring, are the below:

Man-woman equality

Any given great-grandmother is just as important as any given great-grandfather…

Devaluation of the surname.

Because, someone, somewhere, could have been a woman, and then I’d have a different surname, which I’d cherish as much as the one I have now…

…even if I’ve inherited my surname from that great-grandfather.

Disconnection of family history with surname history.

64 ancestors, 64 names (except if we have the cases of knowing or unknowing incest mentioned above). Only one prevails. Why?

Those 64 people your existence connected 170 years after their birth, are all equally responsible for your existence today.

Emergence of local roots and emmigration. Abolition of national false pride.

If I filled in my own mandala, one quarter of it would have lots of “Smyrni”/”Izmir” in it, which would soon dissolve in the depths of Turkey (and who knows where else… the city was the “New York of the Eastern Mediterranean” at its time, after all). Another half of it would have “Australia” writtern all over it but even that would turn into England, even Wales if my sources are correct, the further back I went. Again, who knows what else.

Who knows what 64 parts of the world I’m from?

Is one born or does one become Greek? Hm… Good question. My father got his Greek citizenship after he had lived in Greece for more than 20 years — what is he, Australian or Greek? Similarly, many 2nd generation immigrants, young and old, choose to be Greek because they were born and grew up in Greece. Their children — the 3rd generation– will probably search for the roots their grandparents abandoned by force, while they themselves will by then be indistinguishable from “normal” Greeks. This has happened countless times in Greece’s history. Before the Albanian emmigrations of the early ’90s, there had been many others, centuries ago. The same holds true for the Asia Minor Greeks who were treated like Turks when they first arrived to the shores of Attica and Macedonia but are now bragging about their “macedoniality”, even if their ancestors haven’t been living in Macedonia but for 2 or 3 generations (Google Translate is acceptable for this page), from 1922 onward. On the contrary, they might cut their emmigratory personal history short or forget it altogether as they prefer feeling descendants of Alexander than “merely” Greeks from Pontus, Asia Minor, Capadocia etc. Besides, the national sentiment must stand high and proud against the menacing FYROMites, North Macedonians or what have you… Just remember that those Macedonians might be more Macedonians than the Macedonians. Not descendants of Alexander or some other pitiful misguided conclusion, mind you, no: more Macedonians than the Macedonians because maybe their family has been living in the general region called Macedonia for centuries. Have I come across as wanting to be controversial? Mission accomplished!

Naturally, it’s not just Macedonians, Albanians, Pontians or other more recent immigrants that have decided that Greece should be their home country. Vlachs, Arvanites, North Epirotes, catholic Greeks of Syros (and other catholic islanders) and many others who were and are some of the greekest of Greeks, are now treated as minorities in the Greek state which is trying so hard to retain its purity and its Single Story. In vain of hatred, discrimination and national complexes, we all sacrifice eachother’s family tradition. We have no IDEA of our history and thus we believe the first simplistic fairytale we come across. THAT’s what national identity is about: leveling out and simplification. It’s a goat herder’s pen with the minimum common denominator of historical ignorance as its criteria. It comes as no surprise then that being historically ignorant we learn to disrescpect and even hate, again and again, generation by generation, all that is different — a deviation with which we might have common roots or even be descended from, more or less. Wise were the words of George Bernard Shaw: “Patriotism is, fundamentally, a conviction that a particular country is the best in the world because you were born in it.”

A better understanding of our individual family history can help us be a little more sceptical when dealing with simplified and kitsch national stories. It might help us see that our home town or country is of course very important when it comes to our identity but is not more than a point in time and space which is significant to us just because it is our own. In the age we are going through, let us not allow oral history, that of pain, emmigration, pain, co-existence and complexity be lost under the weight of national epics.

Never allow others to force your roots down your throat: discover them on your own.

The roots are tangled, the past is mysterious and complex.

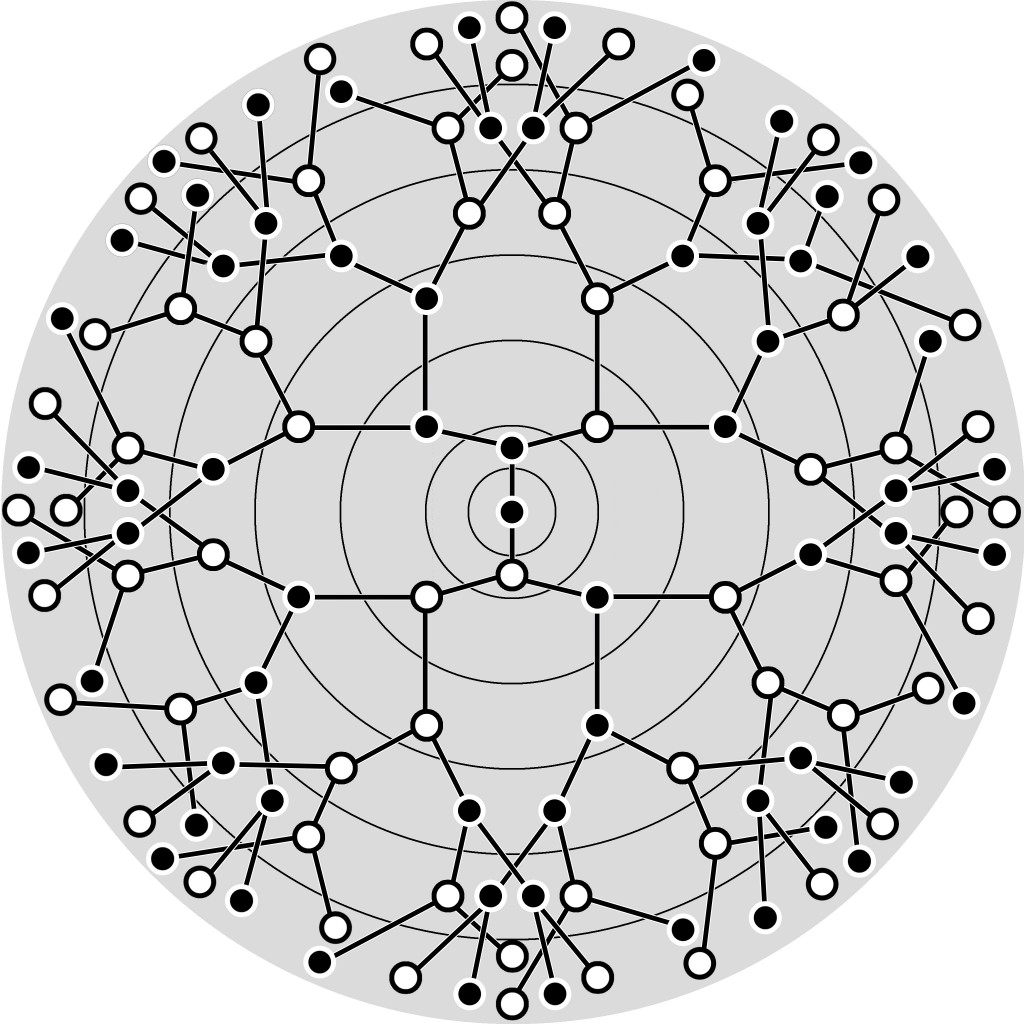

Of course, the above isn’t at all easy to pull off. The more back we go, the more difficult –in a gemetrical progression– it becomes to keep track of everyone! Perhaps in future generations, now that we record everything, it will be easier for our great-great-great-great-great-grandchildren (if we of have any, that is, for there’s also the problems of aging population and infertility…) to find us. The cases, however, of people who are alive now and know where the ancestors of their great-grandparents were from, are few and far between. We can rarely go back more than a single century, let alone two or three. This mystery, as forbidding as it might feel, is just as worth it to embrace and accept. In the example mandalas this is clear: the 7th generation is appropriately mixed up and it becomes more obscure(?) and harder to keep track of. But that’s just the way it is.

As you set out for the Past…

Creative freedom.

I think it’s very important for us to be able to colour all aspects of life and beautify them as each one of us sees fit, for us to be free to create even with and on the simplest of things.

Mandalas don’t have too many rules and they are simple enough. I don’t believe that any special kind of artistic inclination is needed for anyone to fill in their own genealogical mandala exactly the way they like.

By far the toughest part of making our genealogy into a mandala will be to give it a soul and substance, for it to be a work as beautiful as it might be complete with meaning, a piece of cultural representation that will satisfactorily represent its own story.

I put my trust in us.

Here is a blank mandala in the circular shape of the second image. Print it out or open it on Photoshop and…

…happy creations!

Bastion – The Singer (Zia’s Song) Remastered

Also known as: “Build that Wall”.

Playing Bastion these slow, hot summer days nights. The day I was waiting for finally came, that is, the game to be on a ridiculous sale on the Steam summer sales: €5+ for the game and the soundtrack. What a steal. Almost as big of a steal as this song’s picking of my insides. Truly a great moment when it is first heard in-game.

Why Nikola Tesla was the greatest geek who ever lived

Hard Sunshine

This is the song of robotic cicadas.

30×30

A guy that just turned 30 gives his 30 pieces of advice, or what he wished he knew 10 years earlier. More than half of them I feel I have already come to realiseon my own and can heartily agree with most of the rest. That is to say, my personal 23×23 wouldn’t have looked much different. Where does that put me? Lip-smackingly mini-book/piece/blog nonetheless.

The Sad, Beautiful Fact That We’re All Going To Miss Almost Everything

Source: NPR

The vast majority of the world’s books, music, films, television and art, you will never see. It’s just numbers.

Consider books alone. Let’s say you read two a week, and sometimes you take on a long one that takes you a whole week. That’s quite a brisk pace for the average person. That lets you finish, let’s say, 100 books a year. If we assume you start now, and you’re 15, and you are willing to continue at this pace until you’re 80. That’s 6,500 books, which really sounds like a lot.

Let’s do you another favor: Let’s further assume you limit yourself to books from the last, say, 250 years. Nothing before 1761. This cuts out giant, enormous swaths of literature, of course, but we’ll assume you’re willing to write off thousands of years of writing in an effort to be reasonably well-read.

Of course, by the time you’re 80, there will be 65 more years of new books, so by then, you’re dealing with 315 years of books, which allows you to read about 20 books from each year. You’ll have to break down your 20 books each year between fiction and nonfiction – you have to cover history, philosophy, essays, diaries, science, religion, science fiction, westerns, political theory … I hope you weren’t planning to go out very much.

You can hit the highlights, and you can specialize enough to become knowledgeable in some things, but most of what’s out there, you’ll have to ignore. (Don’t forget books not written in English! Don’t forget to learn all the other languages!)

Oh, and heaven help your kid, who will either have to throw out maybe 30 years of what you deemed most critical or be even more selective than you had to be.

We could do the same calculus with film or music or, increasingly, television – you simply have no chance of seeing even most of what exists. Statistically speaking, you will die having missed almost everything.

Roger Ebert recently wrote a lovely piece about the idea of being “well-read,” and specifically about the way writers aren’t read as much once they’ve been dead a long time. He worries – well, not worries, but laments a little – that he senses people don’t read Henry James anymore, that they don’t read Sinclair Lewis, that their knowledge of Allen Ginsberg is limited to Howl.

It’s undoubtedly true; there are things that fade. But I can’t help blaming, in part, the fact that we also simply have access to more and more things to choose from more and more easily. Netflix, Amazon, iTunes – you wouldn’t have to go and search dusty used bookstores or know the guy who works at a record store in order to hear most of that stuff you’re missing. You’d only have to choose to hear it.

You used to have a limited number of reasonably practical choices presented to you, based on what bookstores carried, what your local newspaper reviewed, or what you heard on the radio, or what was taught in college by a particular English department. There was a huge amount of selection that took place above the consumer level. (And here, I don’t mean “consumer” in the crass sense of consumerism, but in the sense of one who devours, as you do a book or a film you love.)

Now, everything gets dropped into our laps, and there are really only two responses if you want to feel like you’re well-read, or well-versed in music, or whatever the case may be: culling and surrender.

Culling is the choosing you do for yourself. It’s the sorting of what’s worth your time and what’s not worth your time. It’s saying, “I deem Keeping Up With The Kardashians a poor use of my time, and therefore, I choose not to watch it.” It’s saying, “I read the last Jonathan Franzen book and fell asleep six times, so I’m not going to read this one.”

Surrender, on the other hand, is the realization that you do not have time for everything that would be worth the time you invested in it if you had the time, and that this fact doesn’t have to threaten your sense that you are well-read. Surrender is the moment when you say, “I bet every single one of those 1,000 books I’m supposed to read before I die is very, very good, but I cannot read them all, and they will have to go on the list of things I didn’t get to.”

It is the recognition that well-read is not a destination; there is nowhere to get to, and if you assume there is somewhere to get to, you’d have to live a thousand years to even think about getting there, and by the time you got there, there would be a thousand years to catch up on.

What I’ve observed in recent years is that many people, in cultural conversations, are far more interested in culling than in surrender. And they want to cull as aggressively as they can. After all, you can eliminate a lot of discernment you’d otherwise have to apply to your choices of books if you say, “All genre fiction is trash.” You have just massively reduced your effective surrender load, because you’ve thrown out so much at once.

The same goes for throwing out foreign films, documentaries, classical music, fantasy novels, soap operas, humor, or westerns. I see people culling by category, broadly and aggressively: television is not important, popular fiction is not important, blockbuster movies are not important. Don’t talk about rap; it’s not important. Don’t talk about anyone famous; it isn’t important. And by the way, don’t tell me it is important, because that would mean I’m ignoring something important, and that’s … uncomfortable. That’s surrender.

It’s an effort, I think, to make the world smaller and easier to manage, to make the awareness of what we’re missing less painful. There are people who choose not to watch television – and plenty of people don’t, and good for them – who find it easier to declare that they don’t watch television because there is no good television (which is culling) than to say they choose to do other things, but acknowledge that they’re missing out on Mad Men (which is surrender).

And people cull in the other direction, too, obviously, dismissing any and all art museums as dull and old-fashioned because actually learning about art is time-consuming — and admitting that you simply don’t prioritize it means you might be missing out. (Hint: You are.)

Culling is easy; it implies a huge amount of control and mastery. Surrender, on the other hand, is a little sad. That’s the moment you realize you’re separated from so much. That’s your moment of understanding that you’ll miss most of the music and the dancing and the art and the books and the films that there have ever been and ever will be, and right now, there’s something being performed somewhere in the world that you’re not seeing that you would love.

It’s sad, but it’s also … great, really. Imagine if you’d seen everything good, or if you knew about everything good. Imagine if you really got to all the recordings and books and movies you’re “supposed to see.” Imagine you got through everybody’s list, until everything you hadn’t read didn’t really need reading. That would imply that all the cultural value the world has managed to produce since a glob of primordial ooze first picked up a violin is so tiny and insignificant that a single human being can gobble all of it in one lifetime. That would make us failures, I think.

If “well-read” means “not missing anything,” then nobody has a chance. If “well-read” means “making a genuine effort to explore thoughtfully,” then yes, we can all be well-read. But what we’ve seen is always going to be a very small cup dipped out of a very big ocean, and turning your back on the ocean to stare into the cup can’t change that.