A few weeks ago, in October, I was discharged from my mandatory military service in the Greek Army. When it was still lying ahead in the future, it was a period I had since forever been quite nervous about: how would I react to being ordered around? Would I be able to do the things asked of me? Was it really okay to support such a violent system with my consent and voluntary submission?

These thoughts troubled me enough that I was postponing the moment I would take the plunge. I was making excuses on the way and calling it indecisiveness, not to mention I was devising ways to avoid serving altogether. Nonetheless, I remained trapped somewhere between being a conscientious objector and indeed believing that even serving in the army could turn out to be a net positive, enriching experience. Sure, friends and people in my environment would often say things like “going to prison might be an enriching experience in some way too, but that’s no reason to go” and I would agree. But then I would think that if going to prison was obligatory for all men over 18 and not just convicts, if one got to see new places and it was only for 9 months, it wouldn’t be prison anymore.

What exactly did it turn out to be though?

This won’t be your typical post-service post. I won’t be writing down too many of my more fun or surreal army stories – people who’ve been through the same ordeal have heaps of their own and for everybody else it just isn’t all that interesting – nor will I list all the reasons the Greek Army is evil/inefficient/irrational/fascist and shouldn’t exist – you could fill in the gaps yourself and be spot-on without any of my help. No, this will be a post about the whole “net positive, enriching experience” part, and how in the end aiming to do something I would never normally do – something I predicted would help me grow – worked just as intended.

These, then, are the ways I grew.

Taking a step outside the Bubble

Spending a part of my life in the army was an experience I now share with many other Greek men and it will always serve as an emergency source of small-talk material. Keeping that in mind, it’s no accident that in the army itself all you talk about with most people is the service itself.

Out in the real world, you more or less get to pick the people you spend time with. The criteria by which you choose those people are mostly hidden away in the depths of your psyche, but you can count on the fact that the people you voluntarily allow closer to you aren’t that different from you. Over time, this might lull you into believing that people in general aren’t that different when it comes to opinions, tastes, political and religious beliefs, etc.

This familiar environment is your bubble (link goes to a TedSummary page of a relevant talk on how we should “beware of ‘filter bubbles’“) Your bubble does a great job at sheltering you from what’s out there, but it also does a great job at sheltering you from what’s out there. Since us humans typically tend to normalize our experience and often fail to, or carefully avoid, taking into account all the unfathomable richness that exists just outside of it, pretty soon we lose perspective, forget about how our experience is completely subjective and far from shared, and we inevitably end up focusing on the (small) anomalies and deviations that exist inside our own environment/bubble and magnifying them to look much much more important than they really are.

Now, the army forces you to spend time with people in bubbles of all sorts of colours: green, brown, khaki, red, black, blue, white, red-and-black, blue-and-white, rainbow, and so on. These are people with whom under ordinary circumstances, out there, you would never ever have any meaningful interaction. They would never penetrate your bubble; it would filter them out of your experience or, in worst case scenario, make sure they are removed if they somehow end up too close.

Meeting, talking to, working with and receiving feedback, compliments or criticism through bubbles different from your own make you realize where the people who watch MAD Greekz all day, people who talk about football any chance they get or whose contribution to most political discussions is “all we need is another good dictatorship” have been hiding. They haven’t been hiding, and it wasn’t that you weren’t paying attention, either: the bubble was just doing its job rendering them invisible to you.

Laid out in these terms, you might ask if the bubble isn’t the greatest thing ever. To be sure, blocking out the majority of what’s going on out there has its benefits. It can help you focus. It can help you stay sane. Still, waking up every once in a while to the fact that there are so many different kinds of experiences, priorities, worldviews, so many bubbles to which you are invisible, can help you, give you the impression at least, that you understand the world just a bit better.

To illustrate, it can be a great and soothing feeling looking at your environment and believing that e.g. vegetarianism or feminism are catching on and are starting to become influential (which is of course true in a way) but definitely not to the degree one might be led to believe if one hangs out, online or off, with people who care about these issues enough they can create an online echo chamber.

Having your bubble burst – yep, I just went there – can bring about a reality check, a harsh reminder of what you really have to come against ( or work with) as well as something which is sorely missing in the lives of most of us: perspective.

(starts at 9:37) “A great wet blanket for smothering the fire of self-conscious anxieties is perspective. Consider the famous advice of Eleanor Roosevelt. “You wouldn’t worry so much about what others think of you if you realized how seldom they do.”As much as you obsess over yourself, you’re not the first thing on everyone else’s minds. They’re worried about themselves, what you think about them, and more importantly, what they think about themselves. You are not the center of their world.

Confirmation bias and its benefits

This next part goes against everything I just wrote about how bursting your bubble is a good thing. But bare with me: paradox is the garnish of life.

In contemporary social psychology, confirmation bias – the tendency to look out for people and ideas compatible with your own existing beliefs, use them to confirm what’s already there inside of you, and somehow miss those who don’t exactly agree with you, i.e. a variation of living inside your bubble – is perceived to be a fallacy to look out for if you want to consider yourself a person of high intelligence. In other words, listening to opposing opinions actively and questioning one’s positions and assumptions builds a stronger mind. So far so good.

Nevertheless, there is one element – a side-effect if you will – of surrendering to confirmation bias that can work well for you if you, like me, are open to considering views very far from your own and as a result sometimes find that weighing too many different opinions equally can get a bit confusing. It is called the backfire effect. Contrary to popular belief, confronting others with hard facts and arguments and proving them wrong doesn’t automatically make them switch over to your side. They might appear to consider your points, but more often than not, opposing opinions will trigger automatic, subconscious defense mechanisms and make people stick to their views and stand their ground with renewed fervour against what they perceive to be an attack against their very person.

It turns out that the army experience had precisely this redoubling effect on my convictions. I used to be willing to listen to completely faulty reasoning or arguments filled with hate and other toxic elements and say nothing because I was half-playing-kind/half-actually-considering the points made. You see, it’s always been easy for me to see why people feel the way they do even if I don’t like or agree with them. When confronted with arguments that made my stomach turn, I would explain away the malevolence through this empathy of mine. It is well-meaning, good for communication and all, but I would sometimes end up questioning my own values as a result: “maybe they’re right. Perhaps being ready for war is the best way to preserve peace”.

I’m known for my relative cool-headedness during discussions, and I do believe about myself that I weigh arguments as fairly as I can. However, the amount of absolute bullshit I was exposed to over the past months at some point made me stop and consider what role I truly wished to have in such discussions. They strengthened my resolve to protect what matters to me the most, i.e. freedom of movement and opportunity, animal rights, compassion, egalitarianism, to name just a few ideas which every day prove to be much less than self-explanatory. I still come to discussions bringing empathy into the picture, but I no longer feel as if a well-spoken argument can leave me stunned, nor that lashing out can solve things, precisely because confirmation bias works the way it does. From an idealistic perspective, I have an easier time recognising what it is I truly have a desire to fight for, or that in some cases fighting is a waste of energy – which by the way is what most online comment wars boil down to.

People end up liking you and remembering you for completely different reasons from what you think

If there was one piece of advice I would hear a lot before enlisting, it was to avoid attracting attention. “You don’t want people to remember who you are, what your name is, or what you do. You want to be a shadow – obedient enough to never raise an eyebrow, yet never to a degree which would make you stand out.”

It wasn’t long before I found out that it was impossible for me not to attract attention, or at the very least have people be somewhat aware of my presence – or absence.

One aspect of this I had been dreading ever since I was still in school, was the unusual sound of my surname – Hall – to Greek ears. I got my fair share of teasing for it when I was a child and for years I wouldn’t be comfortable with the attention I was getting purely because of it. As an adult man ready to enlist, the fear that I would have to fend off teases about my name was still there, like a childhood bite dictates a life-long fear of dogs or some weird aversion to a particular non-threatening food item. What I hadn’t considered was that, even though the army was in many ways like going back to school, a key difference would be that I wouldn’t have to be surrounded by kids anymore. OK, excluding all the 18-year-olds.

No matter where I went, everyone knew who I was: I was the Australian dude. People would greet me or try to engage with me (sometimes in English – just in case I didn’t understand Greek!) and sometimes I would have no recollection of ever talking to them before – they were the successful shadows, come to think of it. Of course I had to repeat the story of where the name comes from an inordinate amount of times, but I realized that the attention I got for my name wasn’t negative – it was my past reactions to it that had made me sort of weary of the whole thing. A few people commented that “Hall” sounded like that of a writer or actor or something like that – possibly because of how similar it is to “Dimitris Horn” – and moved on. All this was a wake-up call for something I should have seen much earlier: my name is a gift. I should use it to my advantage, wear it proudly on my sleeve and not hide behind nicknames invented to protect me from childhood anxieties.

Even more interestingly, people seemed to like me for no reason other than because I was doing what I do and being who I am – kind, considerate, stoic in my duties, accepting, not lacking in curiosity but mostly minding my own business. In an environment like the army’s where people say that you have to fight to survive and that you should not, cannot let anyone take advantage of you without at least busting everyone’s balls in the process first, I didn’t have to do anything to at least get along peacefully with almost everyone. In the end, I stood out not by bringing attention to myself, but by being a sort of a positive, strong silent type figure amidst the chaos, who also happened to have a memorable name. I didn’t have to pretend that I was anything; for all the cringe this line might produce in you, it has to be said: all I had to do in order to get by in one piece was to be myself.

Standing out can be a curse if you lack the belief in yourself that you may deserve or have earned the attention, but the army helped me reverse this in my head. Now I’m happy to say I feel that standing out because I’m actually doing something right, not just because my background is unique, is something to cherish and enjoy.

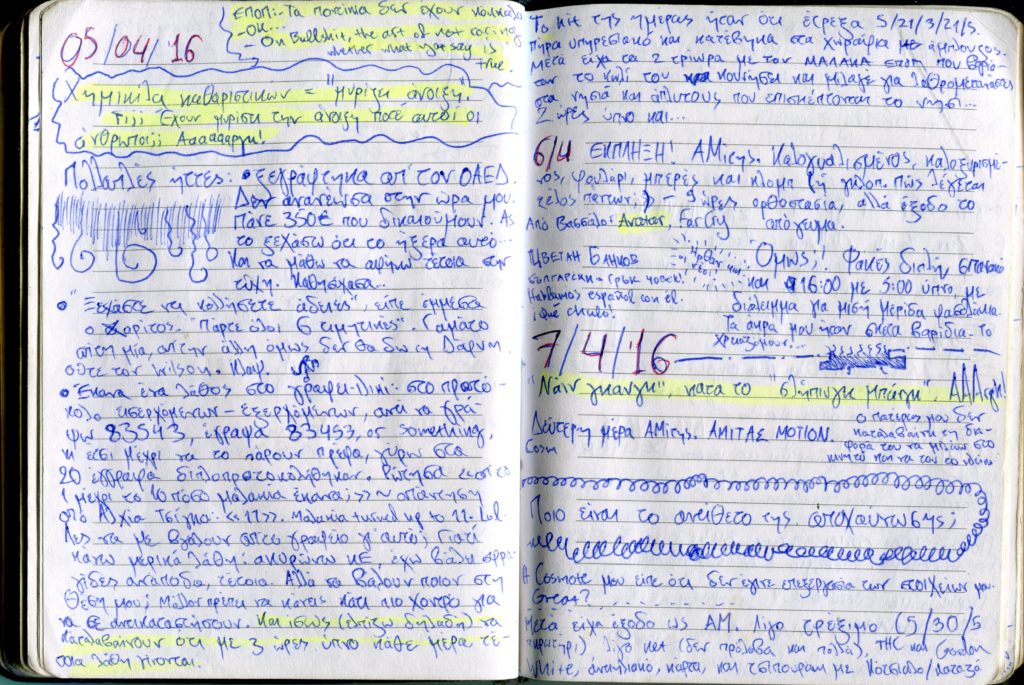

Boredom can be amazing for creativity

The darkest hours, the quietest times and the most boring shifts were the brightest, loudest and most exciting for my creative drive. I always had my little notebook with me, jotting down the events of the day or the ideas that kept coming to me in those fairly infrequent breaks where I could just stand there, alone, mind silent. Whenever people did see me writing down they’d tease me, asking me if I was writing poetry. I’d just smile knowingly, say nothing and keep writing. At the beginning I would just observe, and while it wasn’t interesting exactly, I felt more alive than I had in some time. There was nothing to distract me, no “shiny more interesting thing” to compete for my attention like a lightbulb attracts the butterflies of the night.

In a similar vein, I remember having quite a zen experience one of my first days in boot camp. It was a January Saturday in Mesologgi. Half my platoon was out on leave and I wasn’t on duty, so it was quiet and half as crowded as usual, so I had some free time to relax. It was cold, crisp but clear. The sun had just gone down and I was standing inside looking out at the beautiful twilight, a cup of hot instant coffee in my hands. I only had a dumbphone on me. I realised that, then and there, in my army uniform and enjoying the moment, none of my past experiences, good or bad, really mattered. They mattered only in the sense that together they had brought me to that moment in time, but all that joy and pain was part of the past. The important thing was that I was where I was, simply enjoying being alive and conscious. I was moved deeply by something so profound that had come to me out of nowhere and while at boot camp of all places.

The general lack of stimulus did its wonders on me, at least in the beginning; the first few months I was super aware in my everyday life, and that was something I had been looking forward to before going in. At some point, maybe after the fourth or fifth month, I started using more and more of my time to play video games and tune out from the creeping sensation that I was wasting my time, and from that point on the creativity slowly faded away and was replaced by sluggishness and numbness.

A few days before I started writing this post, I came across the following quote by Neil Gaiman that helps illustrate what kind of experience I had and what energy I’m aiming to bring more of into my life:

According to Neil Gaiman, we should pursue boredom.

“I think it’s about where ideas come from, they come from day dreaming, from drifting, that moment when you’re just sitting there… The trouble with these days is that it’s really hard to get bored. I have 2.4 million people on Twitter who will entertain me at any moment… it’s really hard to get bored. I’m much better at putting my phone away, going for boring walks, actually trying to find the space to get bored in. That’s what I’ve started saying to people who say ‘I want to be a writer,” I say ‘great, get bored.’”

Lack of sleep can alter you consciousness in interesting ways

The biggest downer in the army by far is the chronic lack of sleep. Especially in Samothraki, there would be some extra busy weeks where I’d seldom sleep more than 3-4 hours per day, sometimes less than that. Having to wake up for guard or patrol duty at 23:30, go back to sleep at 2:30 and then have to wake back up at 05:30, apart from all the blunting it brought to my mental acuity, messed with my head in strange and interesting ways.

I recall I would wake up and wear my uniform in a semi-conscious state, neglecting to wear parts of gear or sometimes even take my rifle with me, and then having all kinds of random memories and songs pop up. Once, this song came back to me along with all the lyrics. I hadn’t listened to it for close to 10 years, yet I remembered it almost perfectly. My switched-off state allowed it to come through piece by piece, unobstructed. It’s a testament to the power of music for language learning and the power of burried memories in general. Hypnotism must work in similar ways.

Respectively, getting used to waking up 4:30am every day as I did closer to the end of my service, when I was in Athens and serving as a driver for a general whom I had to pick up from his place and take him to the army HQ and back, helped me realize the power of going to sleep and waking up very early. Being awake for four hours already before the day breaks fills you with an eerie energy, and I’m saying that as a night owl that loves working at night.

Enough. I’ve become another guy who goes on and on about their time in the army – but don’t they say most men can’t avoid feeling at least a bit nostalgic about that period eventually? Memory does work in strange ways, beautifying monstrosities, nostalgifying bittersweet nothings and erasing raw beauty as it does. That said, if you’re dreading having to do a certain something in the future, maybe even joining the army, here’s my distilled perspective, and make of it what you will:

The memory is worth it.

PS: Army post collection in reverse chronological order (they’re in Greek. If that’s a big problem, use Google Translate, at least you’re sure to get plenty of laughs):

HELLO AGAIN FRONTIER ISLAND (15/3)

ΚΑΤΙΤΙΣ ΝΕΩΤΕΡΟ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΕΣΩΤΕΡΙΚΟ ΜΕΤΩΠΟ (26/2)

Most of my writing in the army in the end was about Earworms and book reviews. I can’t be bothered linking to them, there’s way too many of dem posts. I have to admit that sitting here now though, I’m impressed at myself that I had the dedication to review books on leave.