Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino

Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Zenobia, the city on stilts. Vitoriana first told me about this book and sung its praise by describing the mental picture of this city in particular.

Invisible Cities is another of those difficult-to-review books I’ve been going through lately, although perhaps “trudging through” would be a more accurate description. Another one enjoyed in audiobook format, too, and another one I couldn’t concentrate on and retain as well as I would have liked. I have walking, running, wandering through wheat fields, traversing rocky capes and enjoying less-or-more-than-imaginary landscapes in Samothraki to blame. Or it could just be my complete inability to focus on three things at a time—in this case my ears, my visible eyes, and my inner eye. It does sound just a bit too much, now that I mention it.

What I can say is that Invisible Cities turned out to be a very interesting idea of a book—or is it a book of an idea? Marco Polo visits Mongol leader, tells him of his travels to incredible cities far and wide—most of them named curiously similar to ancient-sounding Greek and Latin female names, some rather common in Greece even today—and proceeds to have deep discussion with the Mongol leader (sounds a bit oxymoronic as I’m writing it) on the nature of language, experience, travelling, story-telling… the general business of empire-ruling and noblesse.

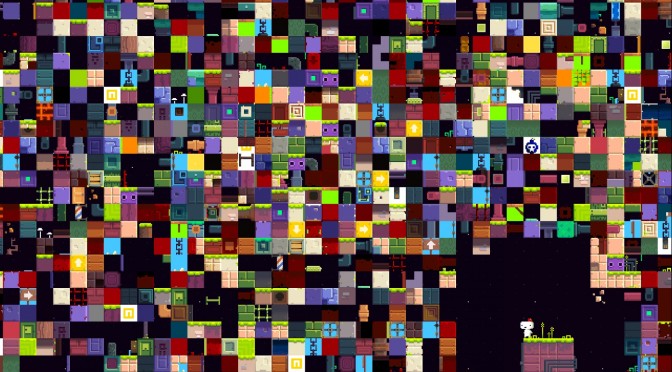

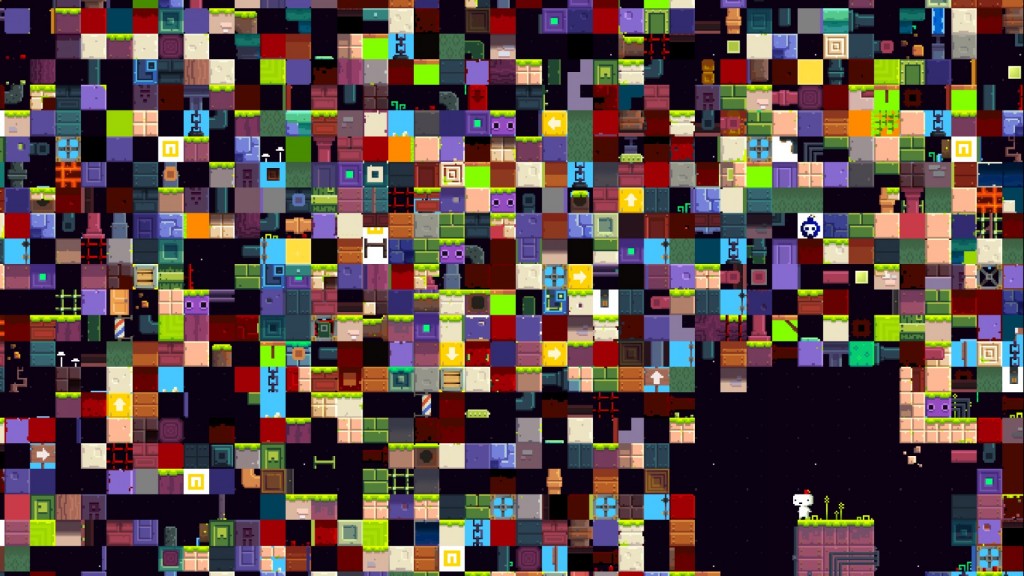

Those invisible cities of Marco’s all have some distinctive fantastical characteristic: one’s buildings have no walls, the pipelines defining the cityscape; Zenobia, pictured above, is built on stilts (like Venice, just without the water—Venice, as Marco Polo’s hometown, also plays a rather central role in this book, perhaps as the archetypical invisible city bar none, just as big a mystery to Kublai Khan as the rest of this book architectural and cultural urban menagerie); another still is a meeting place for merchants who trade stories instead of wares. One city is special in that all visitors remember it perfectly just by visiting it once, while another is its visitor’s memories of it. And so it goes.

Invisible Cities is highly structured yet defies usual narrative conventions; it is abstract, exploring imaginary realities through the kind of what-ifs I’ve most often found in science fiction, yet it does so by looking at human history and existence as a whole, rather than at just its future. Calvino’s language is descriptive while being poetic and profound, inviting the reader’s inner eye to see the Invisible. In all honesty, the vibe I got from this book is that of a geometry-twisting, meta philosophical indie video game in the vain of Fez or The Stanley Parable.

Would Italo Calvino have been a genius game developer had he been a millennial?

Invisible Cities is just one of these books that stands out just from how different and unique it is and how ahead of its time I perceive it today to have been. Or maybe it wasn’t ahead of its time at all: we’ve just internalised precious little about the intellectual zeitgeist of the ’60s and ’70s and the early days of radical postmodernism in literature. Could it be that instead of them being ahead of their time, it’s us who are lagging behind and have progressed less than we think we have, perceiving our intellectual maturity as greater than it actually is?